A high-stakes gamble is playing out in Miami, where a Malaysian developer, the Genting Group, plans to spend more than $3 billion to build what it touts as the world's largest casino.

And that's just the opening bid. Other big names in the gaming industry have joined an effort to persuade Florida to approve what are being called "destination casinos."

But there are many opponents to expanding gambling in the state, including religious groups, hotels and restaurants, and The Walt Disney Co.

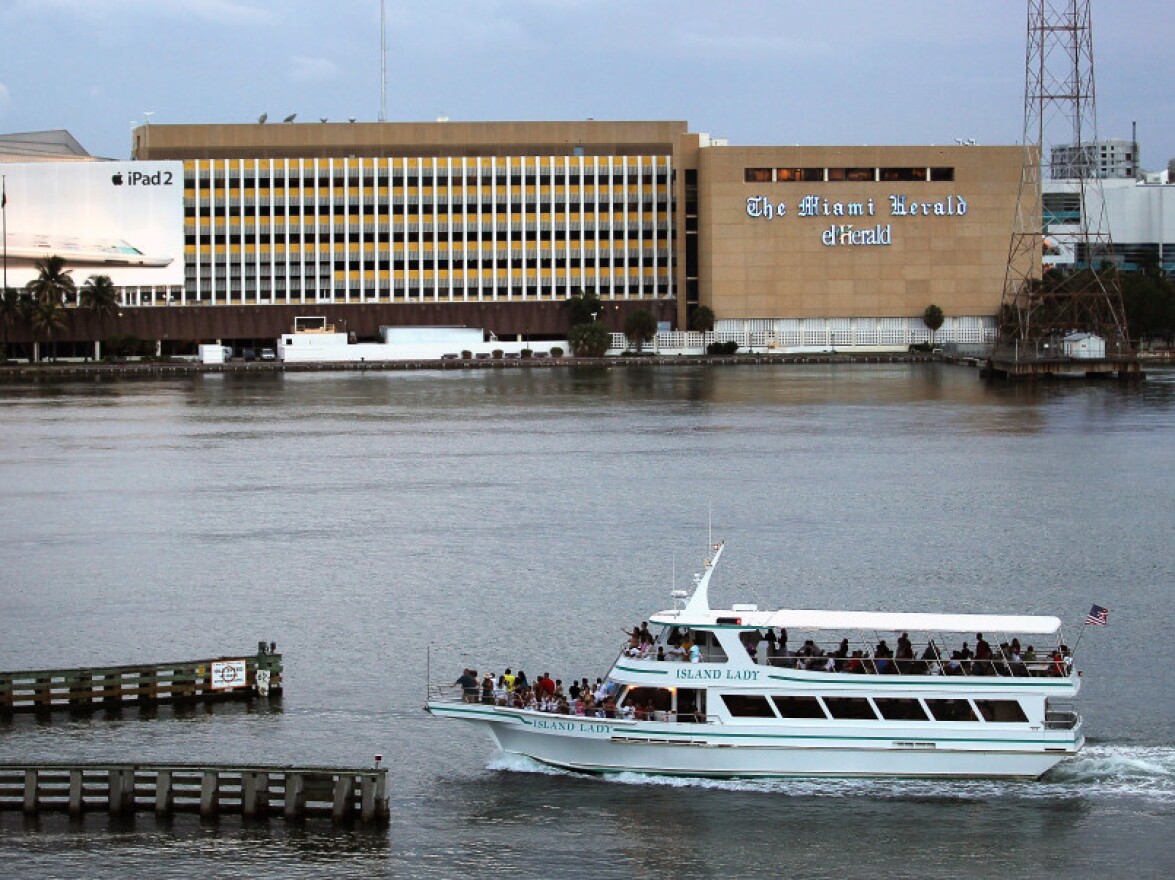

In a promotional video, the Genting Group lays out its vision for Resorts World Miami, a resort that would be the largest ever seen in South Florida. It will "combine iconic architecture, world-class dining and entertainment options," according to the video's narrator — all in the center of the city of Miami, along the shores of Biscayne Bay.

Genting has already acquired prime Miami waterfront real estate and released its proposed design. At its center are six towers with undulating curves inspired by the coral reefs and marine environment of the nearby bay, the developer says.

The development would include three hotels, a convention center, more than 50 restaurants, and a swimming lagoon as large as 12 Olympic-sized pools.

And that's where the questions begin, with the project's size and its main feature: a casino that would be the largest in the world. Except for casinos run by Indian tribes and slot machines at racetracks, casino gambling is currently prohibited in Florida.

Resorts World Miami President Christian Goode says that rewriting state law to allow for three "destination casinos" that cost at least $2 billion each would give a big boost to the region's struggling economy.

"Our initial estimation is that three destination resorts can create 100,000 jobs," Goode says. "We think that, given the climate and the unemployment levels that we see here in South Florida, we see nationwide, we think that's a very important point."

That's the casino developers' lure: jobs and tax revenue. Days after Genting unveiled its plans, lawmakers in Florida's Legislature filed a bill that would allow for three casinos to be built in Miami-Dade and Broward counties.

The casinos would be taxed at a 10 percent rate, delivering, according to one estimate, as much as $250 million a year to the state.

In Miami, county officials are mostly positive about Genting's mega-development. They want assurances that the county gets its share of tax revenue, and that jobs will go to area residents.

But the casinos' critics are concerned about what the development might mean for Miami's economy — particularly for its many hotels and restaurants.

The city manager of Miami Beach, Jorge Gonzalez, told the county commission recently that building 5,000 new hotel rooms adds 1.8 million room nights a year to the area's inventory.

"Now the idea I've been told is that we're not targeting the current visitor," Gonzalez says. "We're going to be bringing new visitors, folks that aren't coming to Miami and South Florida that are big gambling types. Are there really 1.8 million room-nights of those types of people in the world?"

Since the bill that would allow casinos in South Florida was introduced in Tallahassee, opponents have begun to mobilize. They make up a diverse coalition that includes religious conservatives and the Seminole Indians, who operate the Hard Rock Casinos in Florida.

It also includes several business groups, such as Florida's Chamber of Commerce. One of the chamber's leading members, The Walt Disney Co., says it believes gambling is inconsistent with Florida's brand as a family-friendly destination.

The opposition from Disney and the other business groups frustrates State Sen. Ellyn Bogdanoff. A Republican from Fort Lauderdale, Bogdanoff is sponsoring a bill to support the casino, because, she says, it also sets up a state agency that would finally regulate gambling.

She notes that with Indian casinos, horse and dog tracks, and the growth of quasi-legal storefront businesses offering video poker, Florida is already the nation's fourth-largest gambling destination.

"This is the opportunity to actually control and harness it for the first time," Bogdanoff says. "We have a proliferation of gaming in this state, and I don't even know that the public understands just how much it's growing. It's growing tremendously — and it's growing in the wrong direction."

Given the strong opposition, the prospects for Florida's move to open the state to casino gambling look uncertain.

Genting says that it plans to go ahead with its massive Miami resort, whether gambling is approved or not. But the mere fact that the state has put the possibility of new casinos on the table has spurred a frenzy of activity.

At least two other Las Vegas casinos are actively pursuing opportunities in Miami-Dade and Broward counties. And several other counties in Florida are now exploring their own plans for possible casinos.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.